Composer Iman Habibi joins conductor Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra onstage after a performance of his Zhiân Oct. 12, 2023 in Symphony Hall. Winslow Townson photograph

Plato wanted to ban all poets. We might ban musicians as well.

They stirred emotions too deeply, he argued. When great artists express music with empathy, with love and uncommon technique, Plato seems about right.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra, under music director Andris Nelsons with Yo-Yo Ma onstage the weekend of October 12–15, performed the Shostakovich cello concertos: the defyingly virtuosic first; and the second, a deeply ironic lament. Both were composed for Mstislav Rostropovich, and premiered in 1959 and ’66.

Nelsons and Ma each attempted remarks from the stage beforehand, comparing present-day turmoil with the Cold War–anxiety of the composer’s era. The performances—reviewed on the 12th and 14th—were rivetingly dark.

These concerts, like most, had been planned for years. Unplanned was the war in Gaza, which has roiled communities around the world, and which created a flash-mob of emotion during the first performance. Tensions were high, and both soloist and conductor tried to express what it meant to be recalling old terrors in this harrowing new context.

Their words both haltingly and incompletely expressed their ideas. At a second performance, both read deliberately from notes, trying to steady their overflowing feelings.

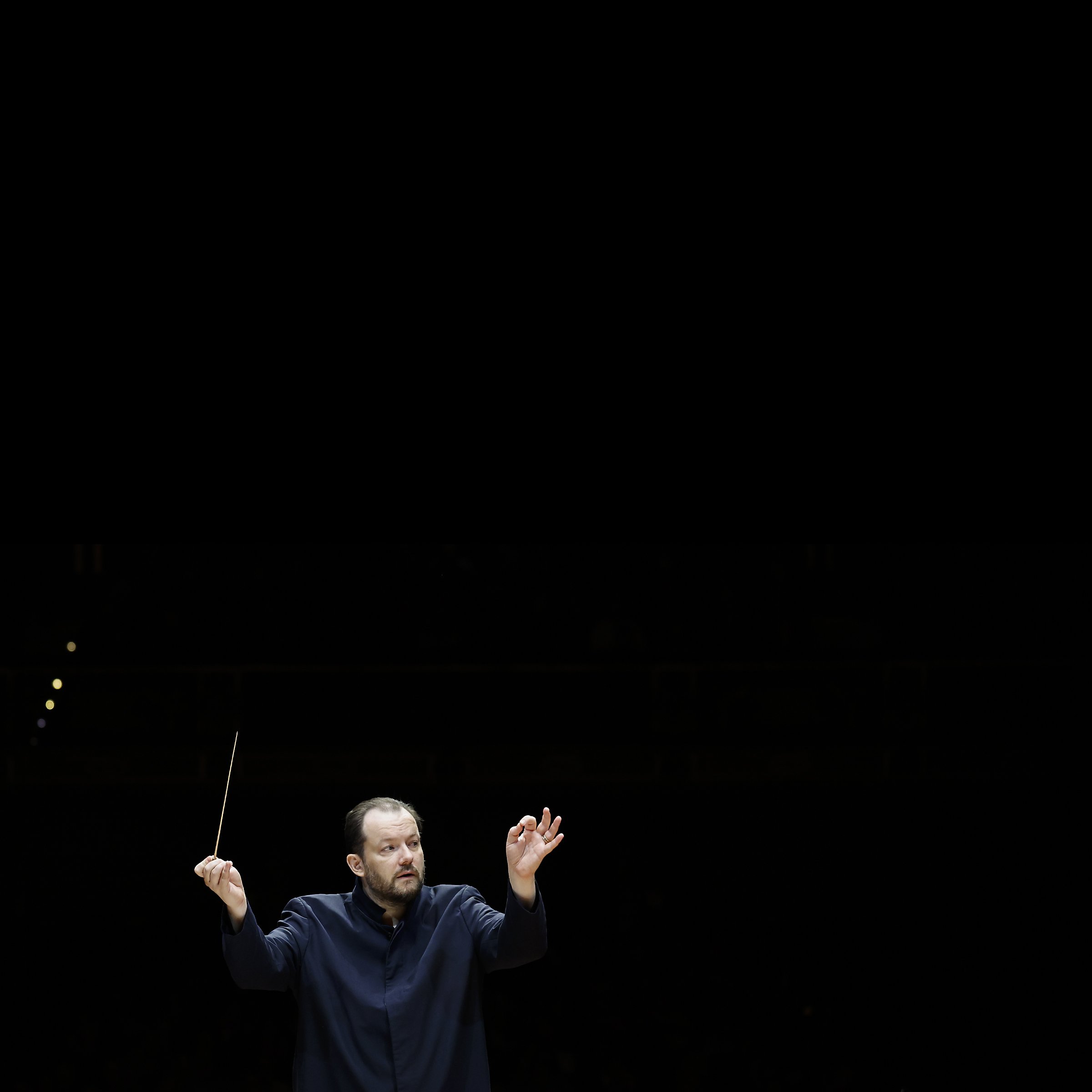

Andris Nelsons conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Oct. 12, 2023. Striking photograph by Winslow Townson

The program began with the Second concerto. The BSO originally performed it on Aug. 10, 1975, with Rostropovich, and Seiji Ozawa on the podium. Shostakovich had died the previous day.

The Second is a soloist’s concerto from the beginning, with a melancholy opening phrase. The orchestra appears in unusual pairings: soloist and bass drum, then tambourine; xylophone, whip.

The last two movements are played together, beginning with a scherzo, which mimics a street vendor’s song, Buy Our Pretzels. The vernacular tune never leaves, contorted into hideous shapes by the soloist and by nearly every section of the orchestra as well. The unusual instrumental pairings persist. At the conclusion, the soloist articulates an extended drone, with wood blocks, whips, snare and xylophone alternating percussive patter behind.

Cellist Yo-Yo Ma onstage with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Andris Nelsons conducting, Oct. 12, 2023. Winslow Townson photograph

There were tears onstage opening night: the soloist, and members of the orchestra. While there was no direct connection between Shostakovich’s Cold War–era struggles, and the war on Gaza’s streets, musically, they seemed as one.

These performances will be recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, a continuation of the BSO’s successful cycle of Shostakovich’s orchestral works. A fifth CD set, released this month, includes symphonies 2, 3, 12, and 13. Three previous releases have garnered Grammys. The piano concertos will be recorded with Yuja Wang, and the violin concertos with Baiba Skride.

Born in Riga, Latvia—a Soviet republic in 1978—Nelsons has spoken of a lifetime of reverence for Shostakovich and his music. This DG/BSO recording project has been perfectly suited to his taste and training.

The program concluded with the First concerto, which also featured BSO principal Richard Sebring prominently. The still-impossible virtuosity of the piece was on display in both performances—but the hyped emotional experience of the first performance was not possible to replicate.

The soloist starts the First with a stylish four-note motif that will recur. A wicked cadenza takes up the entire third movement. The drama—intensified up to the closing cadence, half-a-dozen confident stokes in the timpani—matched the virtuosity on display.

The program also included Iranian-Canadian composer Iman Habibi’s one-movement Zhiân, itself a commemoration of the 2022 death in Iran of Mahsa Amini in custody of the morality police. Habibi is one of too many composers who have grown up without basic musical tools—he learned by mimicking television tunes on a keyboard—but has created his own voice. Habibi’s work was balanced, but simply conceived. Zhiân seemed direct, almost effusive, and certainly more uplifting than commemorative.

Now marking his tenth anniversary with the BSO, Nelsons has mellowed physically. Compared to the gaudy swoops and ice-cream scoop gymnastics of the early years, the hard-working Nelsons seems almost reserved now. In Haydn’s Symphony No. 22, Le Philosophe, which opened the program, Nelsons took whole phrases off, simply admiring his sections with trust.

Yo-Yo Ma’s grace has always extended to his stage-mates. As an encore, he engaged the entire cello section in an arrangement of the Prelude to Shostakovich’s gentle Five Pieces. He sat alone in a back desk, and let principal Blaise Déjardin lead the section and the audience to a quieter place.